Story-Seeking the Sunless in the Seas & Skies

London falls and rises. Humans explore the world. Shadows lurk. The sunlight burns, though the dark is rarely what it burns.

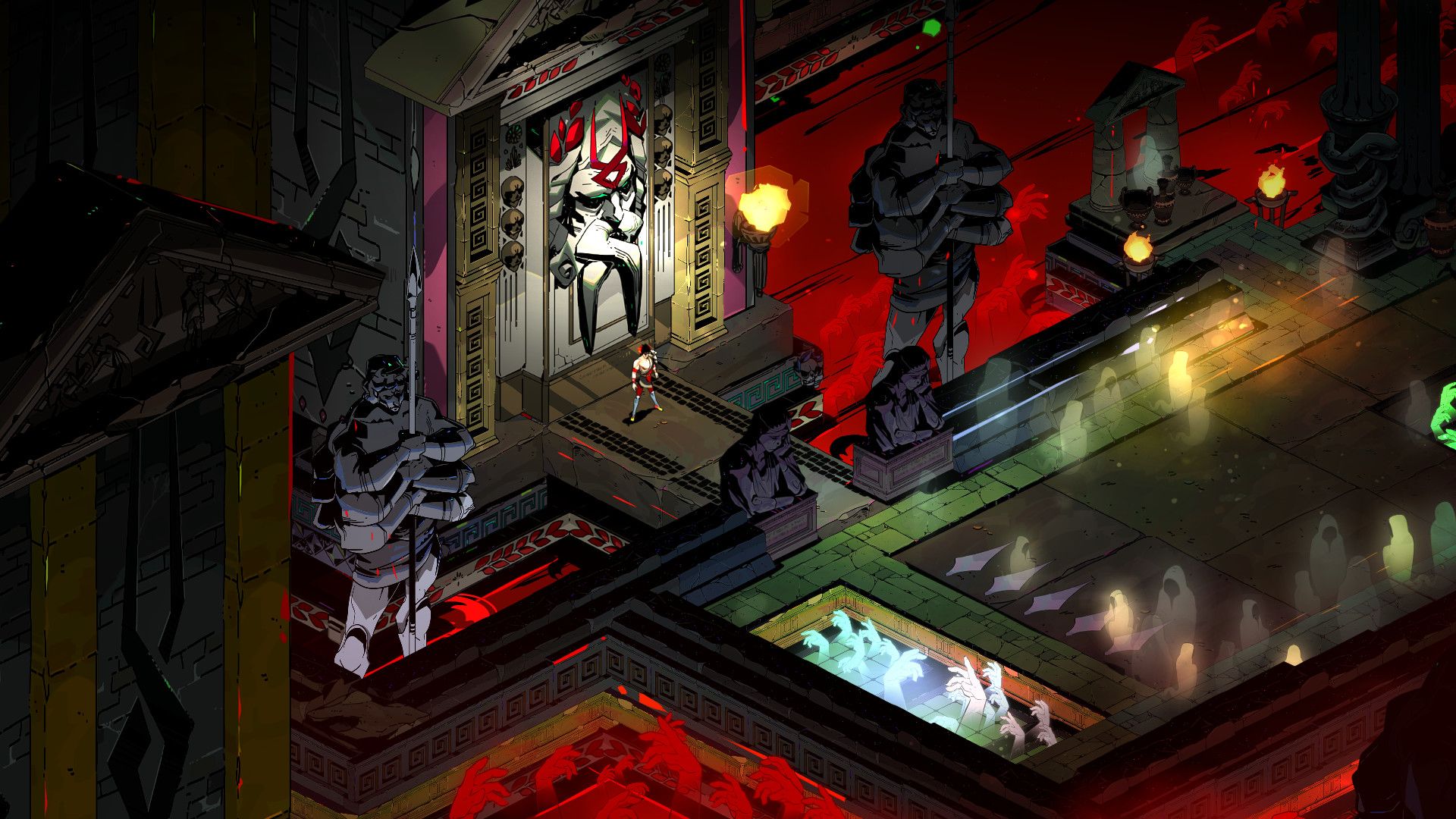

Sunless Seas and Sunless Skies are two story-exploration games focused on the Fallen London series, a humorously macabre twist on a turn-of-the-20th century gaslamp London. I don't wish to review the gameplay here; there's enough reviews on Steam and the web for you to form an opinion there. Instead, I want to look back on the stories the games tell and how the themes contrast, despite both ostensibly being "horror and humor." There are generalized spoilers for both games, but I try not to spoil specific storylines.

Why?

- I can't get these two games out of my head

- Compare and Contrast two excellent worldbuilding attempts, one which I feel lands, one which does not

- I think reviews are overdone, and want more analysis not in video form

- I can't get it out of my head

- THESUNTHESUNTHESUNTHESUNTHESUNTHESUNTHESUNTHESUNTHESUNTHESUNTHESUNTHESUNTHESUNTHESUNTHESUNTHESUN

Your primary interaction with the world is exploration. The Sea and Skies move around and nothing is quite where you remember it. At points of interest, you may find different snippets of stories based on the crew you have, the items you're carrying, or how sane (or in-) you may be.

This leads to very personalized playthroughs for each person. Perhaps the character that became Wistful in your playthrough was Regretful in another's. Even mimicking decisions from run to run ends up with differences, as there are skill checks and random elements and they may span tens of hours. While this "reset" might initially be dismissed as a quirk of gameplay, there are enough cosmic horrors within the Sunless worlds to believe that all of these stories have and will happen. It reminds me of the SCP Foundation, which formerly used to have no "set" canon, but now has multiple competing canons, of which authors have intended certain core concepts, but the reader is still free to pick and choose.

Why start here? It changes the themes you see. Perhaps your captain dances the knife-edge of madness, and your decisions have no rhyme nor reason. Perhaps you're a surface dweller who doesn't believe any of the nonsense that those in the Neath tell tales of. Or maybe you were born in the Neath and just want to trade to get by, and not think about all the horrible ways you can die. All have different feelings and will impact your run accordingly, but overarching themes remain constant.

What is the Unknown?

Horror, as a genre, focuses on the unknown and unfamiliar [citation needed]. The less you understand something, the more power you give it over you. This ranges from the simplistic: a monster in the night chasing you ("Maybe it's a friendly dog? Maybe it's a werewolf!") to the existential ("What if we are simply a simulation and the plug might be pulled at any time?"). But, the mere existence of a monster is, in itself, not horrifying. The circumstances of their creation might be, as in Frankenstein, but complex horror focuses on humanizing the monster.

The Sunless games are not filled with jumpscares. The monster in the dark is waiting, and will find you, but might just want to share their tea and biscuits with you. More likely, you'll run out of fuel in the middle of your explorations - easy prey for scavengers, bandits, and monsters of the deep or sky.

Sailing the Sunless Sea, horror awaits at every opportunity. Sometimes it lives comfortably in your cabin and crew, going slowly mad in the dark as terror builds and the Unknown lurks. Perhaps it waits for a chance to seize you in a fit of insanity, only for you to wake and find a crew member missing but more supplies available for your remaining crew. At other times, the horror lurks merely feet under the water. Watching you, waiting for a slip in your diligence, ready to pounce and swallow your ship whole in the everlasting night. You walk a narrow path as Captain, desperate to achieve some greater glory, but cognizant of the horror that follows you. No one has trod where you go and told tales, no one has prior knowledge. Thus, you explore at your own peril, worry about your crew, and try to make it to the next port, an unknown distance away.

Conversely, in the Sunless Skies, the great metaphor of railways connecting people and conquering the vast wilderness lives at the forefront of the Skies. But it poses a challenge - you follow in the tracks of those that have come before; this is the nature of rail, you cannot go where there are no tracks, and so someone must have explored. Tales have been told, lands conquered, and monstrous beings killed. The loss of human life, therefore, merely becomes a statistic in the grand fabric of this new world, the kind of incomprehensible horror that our mind simply shuts out to protect us from breaking down about our fellow human beings.

Themes

Both of these works explore the kinds of horrors that can spawn from the unknown, but approach their worldbuilding in fundamentally differently ways. Seas plays with the familiarity of the known and unknown, keeping you off-balance as you learn about this new portion of the world hitherto unexplored. Your captain is part of the great tapestry that makes up the story. In Skies, though, we see that the Unknown is only unknown to you; the fantastical is shackled, corralled, and subjugated by greater powers. The role your captain plays in this world is reduced, eking out a meager existence in between titans of industry.

Focusing on Seas, the Zee is familiar - sailing an ocean is deeply rooted in our cultural consciousness, but you quickly find your intuition misguiding you. Approaching the unknown with trepidation, you may think all things are out to get you, but find some of the scariest things can be the friendliest (or at least what passes as friendly in this world).

We find monsters and humans living side by side. A colony of those that cannot die, their bodies colonized by moths. Golems that have their own free will. Honey made by bees that eat memories of humans. Apes that amass souls and have formed a caste system around them. Devils that trade in souls and wouldn't you just be a bit lighter without yours? In each of these places, you're met with creatures acting very human. Whether they're dealing in business, forming relationships, or just living, many of them don't seek to hurt you in any way. You may become hurt by interacting with them in negative ways, but is that not true of humans, as well?

On the other hand, we find groups of humans that seem perfectly reasonable, but might have nefarious purposes. Smugglers, graverobbers, murders, insular groups that exile members that make mistakes. Frequently, determining who might mean you harm is no clear task, and Failbetter Games are careful to ensure that Dark Is Not Evil. There's an exploration of what it means to be sapient, to have agency in the world, and what you do with that agency.

The music throughout reinforces this - each area has its own theme, and musically it ranges from dramatic and tense (Infernal) to the melancholic (Storm, Stone, Salt) to the cheerful (Submergio Viol). It reflects the wide range of peoples and experiences, and many of the tunes might even be described as cheerful - people, whether monstrous or not, have always found ways to celebrate the light they cast on the world. Many of the remaining themes are contemplative, urging you to think about where you are and what it means to be the peoples living in the Neath.

Thus can the familiar feel unknown, and the unfamiliar feel known. Appearances and language can be deceiving, and it might require the same kind of investment to truly understand a person in the Neath as in the real world. By playing with what is perceived as familiar, you are kept off-balance, tense, worried for what the future trips might mean, or whether you've set sail for the last time. Entities vie for power, but no one has a clear picture of the state of the world, least of all you. This allows wondrous questions like, "Do pawns of those powers play their roles because they don't know what else to do or because they don't know something is wrong?" Many times the impact of your actions is left intentionally vague, leaving both player and captain wondering whether they aligned with their morals.

Alliances are frequently permanent - for a given captain - and decisions will lock you out of various story paths. The political machinations of the various denizens of the deep churn on, each attempting to gain power over their allies and enemies. London has established itself as a powerful force in the Neath, but is still the newest piece on the chessboard. Even within London, factions vie for favor, urging you to further their goals and if you could, just not talk to that gentleman over there? For anyone who follows geopolitics, the moves are familiar, even if the pieces might have sprouted a tentacle or two. I'd also wager that most are unaccustomed to the board consuming pieces, too.

Meanwhile, the "rail" lines of the Skies are also filled with questions and the unknown, but the fantastical element has been reduced to rote. We go back to the metaphor of rail: they are predictable and smooth, providing swift passage. Given the nature of the game (a flying locomotive), there's plenty to explore, like the mountain that contain rocks that can be spun into time; the murdered sun, floating listlessly in space; or writing that sears itself into your mind, only to surface later.

But, notably, these are "things" or "events." The peoples of the High Wilderness are mostly human or human-like, and instead of investigating identity or motives, your role is more of a chronicler of fates, understanding how events transpired and where they might go, meddling only little. Whereas on the Sea you may have hope of learning or becoming something more, in the Skies you find that the Powers That Be have ascended into the sphere of the unknown, surpassing all but a few via the familiar exploitations of capitalism. The horror is existential and inward, but loses something in the process. We are well acquainted with the evils that humans can perpetuate, and thus are limited in our exploration of the unknown.

The music reflects this limitation, maintaining a more somber tone throughout. Every song on Skies' OST, from the initial pluckings of The High Wilderness to the comfortable Albion London Lights, has less variation and is more reflective than Seas' OST. It evokes memories of the long trips that you take crossing the empty skies.

Worse, there are few non-humans. The colonization of the High Wilderness by London is well underway, displacing beasts, horrors, and other races alike, but mostly the only non-humans we see are Devils, that crafty race so enraptured with souls. Investigating these stories, we find nothing new about the world. Every location has the detritus of prior explorers. Every horror had its story and is subjugated or shackled. Industrialization permeates the Skies, streamlining the exploitation of anything of value from the fantastic, consuming it to fuel its infernal fires, or discarding it as useless in the name of progress.

And certainly the Skies has power struggles - while London has risen in the world (worlds, perhaps?), the vast majority of the politics you encounter are inter-empire. Londoner against Londoner, as any of the other races or empires that followed from the Neath are relegated to smaller parts in this new world. Whereas the Seas had a tiger in a coffee shop lamenting the current trends of poetry, the Skies merely has another Londoner smoking a pipe in the corner. One of the former (rumoured, as always) greatest powers in London is relegated to a mere traveling companion, lamenting his situation and reduced to checking off remaining items from his bucket list. He tries scaring off your captain, but is not even given a skill check for interacting.

The comparisons could go on. There's an immense corpus of text, and clearly a significant amount of thought behind the worldbuilding. But in Skies, the feeling of wonder and mystery about the world is crushed under the authoritarian boot of a homogenous empire.

Perhaps I am overly sensitive to the comparison. I experienced them closely in time and the tone and theme difference was stark to me, trading the juxtaposition of amused writing and horror (the tutorial for the Seas DLC opens with, "Hello, Delicious Friend") with the dryer, more somber tone of an archivist reading a will of an eccentric ("The light of the Clockwork Sun oozes into your cabin like rancid honey"). Expecting more of the same runs aground of the oppressive weight of history missed, of jackboots turning a corner to catch you for thoughtcrimes, and of a power so terrible and great that your influence on it is less than that of a gnat on a skyscraper.

As previously established, though, no two players are likely to have the same experience - video games are an interactive medium, after all. These themes permeate the two games, but who the player is can be just as important as the character being played.

Player Versus Character

No story is free from the touch of the reader. An author's intent can only go so far, their experiences coloring between the lines of text that dance across a page. But the reader is also touched, their mind sparked on by fantastical prose, vivid imagery, and lurid events.

In games, we see this interaction more clearly than other media. Characters are frequently stand-ins for the player, with little to no development given, allowing the player free reign to ascribe motive and reasoning to their actions. Inevitably, these actions remain constant, as a game is still a crafted experience. The range of expected outcomes is limited, and the experience remains more akin to a movie, with events playing across the screen with timed cadence.

If a character is established, the division of the player and character is made apparent. The character should know things about the world the player does not. This can be a source of dramatic irony. If ignored, it can drag an otherwise well-written piece to ruin, the finely-crafted story beats do not occur when expected, and the order of events may be completely scrambled by the player. Stories are not written for characters but for people who experience them.

But when we discuss horror and the unknown, this becomes a sticking point. All of the characters treating something as completely normal can be a good hook, but if instead the character(s) dismiss it, then it invites the player to ignore it, lest they run headlong into cognitive dissonance. If the actions of the character don't align with the intent of the player, then the experience grinds to a halt, exposed for the construction it is.

When a game like Sunless Seas or Skies has roguelike elements, it automatically introduces a looping structure. In other contexts, this is "solved" either as a pure gameplay mechanic or through characters that are fresh each run through a dungeon, as oblivious to what awaits them as the player. On the other extreme, you may have an explicit time loop, usually one where the character understands what is going on, aligning the character and player in the world. In Seas, the looping structure may or may not be diegetic. The world is strange, people come and go, who can tell the nature of time? Your captain can pass down heirlooms to give bonuses to future captains. The player accumulates more knowledge and in game terms this can be treated as knowing about more and more rumours of the deep.

But in Skies, despite having an identical gameplay mechanic, the accumulation of knowledge never feels quite right. Surely one of the many captains you play must know more about the world they inhabit. Again, the rail metaphor; nothing is new. Increasingly, you find that the horrors of the world are simply human bastardry in a new skin. The exploits of capitalism change little whether you are trading your time as it passes, second per second or instead vast swaths of your literal future away to hopefully provide for your family.

Thus, we arrive at a challenge - if the player's potential interpretation of events are not taken into account, then the story may fall flat or miss the mark completely, especially when the story requires the unknown to drive horror. But if, in the case of a sequel, you can expect players to come in with some existing knowledge, how do you make that accessible to new players? Tradeoffs must be made, and in those tradeoffs, we see how the differing themes can arise.

In Seas, the world is new and unexplored. We are on equal footing with our characters. But in the Skies, the world has moved on, and many mysteries are solved. Not because the authors spelled everything out, but just via continuity providing its own answers. A story need not be cryptic to be mysterious, but spelling it out requires a soft touch, lest you demand no questions from the player. Conversely, leaving it too open invites boredom from the player. If the author won't engage with the world, why should the player?

Leaving Open or Wrapping Up

We arrive back at the competing themes. The unfamiliarity that the player experiences in Sunless Seas is matched by the character - neither of you know what you will find waiting, and the more cycles you inhabit, the more the world becomes clear to those setting sail and to you each loop.

Sunless Skies, in focusing on the colonization and industrialization of magic, crushes the potential horror. After all, why bother focusing on the omnipotent creature that might end your existence with a thought when your boss demands another two years of your life that you might otherwise spend with your child? The mundanity of the horror in Skies works against itself, dissonance seeping through every crack.

Perhaps that's where the real horror lies.